LEWISTON, ID – President Joe Biden today announced at the White House Conservation in Action Summit that his Administration is taking new actions to conserve, restore, and expand access to lands and waters across the United States. These include a proposal to modernize the management of America’s public lands; a plan to harness the power of the ocean to fight the climate crisis; a strategy to better conserve wildlife corridors; new funding to mitigate the loss of salmon and steelhead; improve access to outdoor recreation; promote Tribal conservation; reduce wildfire risk; and more.

Biden says his Administration is establishing national monuments in Nevada and Texas and creating a marine sanctuary in U.S. waters near the Pacific Remote Islands southwest of Hawaii.

As part of his plan, the federal government is launching the $1 billion America the Beautiful Challenge.

“These investments will help meet the President’s goal – set during his first week in office – of conserving at least 30% of U.S. lands and waters by 2030,” according to the White House.

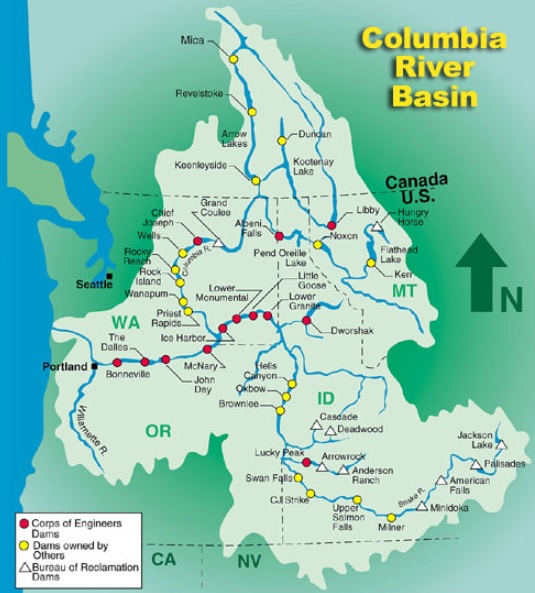

The Administration is also working to protect the Columbia River Basin and its anadromous fish such as salmon and steelhead.

Eastern Washington Congressman Cathy McMorris-Rodgers (WA-05) says Biden’s announcement was a “tipping of the hand” toward the removal of the four Lower Snake River dams.

On March 21, 2022, the Biden Administration convened a Nation-to-Nation consultation between federal agencies and departments, as well as leaders and representatives from the Tribes of the Columbia River Basin. Officials were requested to provide actions to mitigate issues that have caused harm to the ecology of the Columbia and Snake Rivers, their tributaries, and Native Americans.

“From the 1930s to the 1970s, the Federal government constructed a series of 14 multipurpose dams in the Basin to address a myriad of economic challenges, and, additionally, more than 100 non-Federal dams were constructed. Communities across the Northwest have come to rely on these dams for flood risk management, water supply, irrigation, navigation, and recreation and importantly: reliable and affordable electricity,” a White House blog reported a year ago. “The dams also altered free-flowing rivers, affected juvenile fish as they migrate out to sea, impeded adult fish returning to spawn, inundated Tribal fishing areas and sacred sites, and forever displaced people from their homes. In the 1990s, 13 of the Columbia River Basin’s salmon populations required the protection of the Endangered Species Act to survive. We have been working to stem the decline ever since.”

Billions of dollars have been spent, in partnership with Tribes, states, and non-governmental organizations, on efforts to recover salmon and steelhead. The Nez Perce Tribe has been heavily involved in those efforts, as well as for other species such as lamprey and sturgeon.

“These efforts include modifying the operation and configuration of the federal dams to improve passage conditions for fish, investing in hatchery facilities to produce and supplement Tribal and non-Tribal fisheries and improving fish habitat, changing flow augmentation releases from some projects to counteract warmer water, and implanting programs to transport juvenile fish downstream by barge and truck,” the blog added.

One of the proposals on the table is the breaching of the four Lower Snake River dams downriver from Clarkston. Proponents of the 2021 proposal from Idaho Congressman Simpson say the move would return more natural flows to the river and improve anadromous fish runs. Opponents argue it would significantly increase the cost of electricity in the Northwest and hurt the region’s economy, including recreation, tourism, farming, and river transportation.

Located 465 river miles from the Pacific Ocean, the Port of Lewiston (Idaho) is the most inland navigation port on the west coast. Port officials have been outspoken against Simpson’s $33.5 billion plan to remove Lower Granite Dam at a cost of $400 million by 2030, followed by Little Goose ($350 million/2030), Lower Monumental ($350 million/2031), and Ice Harbor ($300 million/2031). In addition to those four dams, there are four dams on the Lower Columbia River that have navigation locks that are used to transport goods and provide tourism between Portland, Oregon and the Inland Northwest. They are operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Pacific Northwest Division.

Simpson’s plan calls for all public and private dams that are licensed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and produce more than five megawatts of electricity for sale in three of the last five years to receive an automatic 35-year extension of their license in addition to their currently licensed period with the total maximum extension length not to exceed 50 years. He says this would go into effect following the breaching of the fourth dam and would eliminate the “slippery slope” argument that “if you allow them to remove these 4 dams they will go after the other mainstem Columbia River Dams and others.”

The plan also calls for mitigation for communities affected by the breaching of the dams. For example, the Lewis-Clark Valley (upriver from Lower Granite Dam) would receive $150 million under the Lewiston-Clarkston Waterfront Restoration; $250 million for Siting, Development, and Construction; and $100 million for an Economic Development Fund. Funding would also be provided for navigation ports, river transportation companies, tourism, and others.

Meanwhile, another key river issue that the Biden Administration has heard about is the complete fish blockage in the Middle and Upper Snake River areas due to the Idaho Power Company‘s Hells Canyon Complex, which encompasses 95 river miles along the Idaho-Oregon border.

“We heard a request to support [the] reintroduction of salmon in areas that historically yielded abundant populations, but are fully blocked by dams lacking fish passage: the Upper Columbia and Upper Snake,” the Administration said in its 2022 blog.

Eastern Washington Senator Mark Schoesler (R-Ritzville) says the fact that the three dams in the Hells Canyon do not have fish passage systems has played a major role in the demise of salmon and steelhead.

Idaho Power has been attempting to relicense Brownlee Dam (1959) Oxbow Dam (1961), and Hells Canyon Dam (1967) through the FERC since the mid-1990s; the license expired in 2005. Until a new one is issued, the company operates the dams on an annual license under the terms and conditions of the prior license. All of these facilities operate under the same license (No. 1971) granted by FERC.

“The final supplemental EIS is targeted to be complete in December 2023, which would put Idaho Power on track to receive a new long-term license in late 2024 or early 2025,” Idaho Power says.

On March 1st, Idaho Power responded to a letter sent to the FERC in January by the Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation regarding the 1980 settlement agreement (section 2.3) which the power company says “permanently” resolved issues pertaining to the number of salmon and steelhead which have been lost or destroyed as a result of the construction and continued operations of the dams. Tribes were reportedly left out of that agreement.

“The simple fact that a new license application is before FERC for consideration is not sufficient justification to relitigate the impact of the construction of the dams on anadromous fish or collaterally attack the resolution of that issue over 40 years ago,” the Idaho Power Company letter says.

Schoesler doesn’t agree.

He believes Idaho officials “grossly undervalued” salmon and steelhead decades ago.

In the late 1950s and the early 1960s, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game reportedly poisoned several lakes in order to plant trout, the Idaho Statesman reported in 2008, adding that barriers were also installed to keep the sockeye out.

At one point, officials say an estimated 150,000 Snake River sockeye salmon made the annual 900-mile trip from the Pacific Ocean to return to the lakes near the town of Stanley, Idaho – including Redfish Lake. Federal officials say the run started to decline in the early 1900s because of the poisoning, dams, irrigation diversions, and overfishing.

On the brink of extinction by 1991, sockeye salmon were listed under the Endangered Species Act.

That year, one sockeye returned to Redfish Lake. Dubbed “Lonesome Larry,” he set regulatory and stakeholder groups into action, resulting in the Redfish Lake Sockeye Captive Broodstock Program, a multi-agency and tribal endeavor according to NOAA Fisheries.

“Initiated to protect population genetic structure and to prevent the further decline of Idaho sockeye salmon, the program pools the expertise and efforts of several collaborators including NOAA, the Bonneville Power Administration, the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, Idaho Fish and Game, and the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes,” the federal agency says.

In 1995, no sockeye returned.

Earlier this month, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife fishery managers predicted the endangered Snake River sockeye run is forecast to increase slightly to 2,600, compared to last year’s return of 2,329 fish.

Meanwhile, Senator Schoesler says Congressman Simpson’s proposal to breach the Lower Snake River dams is effectively a “not in my backyard” type of plan.

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council says prior to the construction of the Northwest’s dams, salmon and steelhead spawned in numerous Snake River tributaries, and fall Chinook salmon spawned in the mainstem of the river including in the Hells Canyon and farther upstream.

“The Clearwater, which enters the Snake at Lewiston, Idaho, downstream of Hells Canyon, and the Salmon in Idaho and Imnaha in Oregon, which enter the Snake within the canyon, supported strong populations of salmon and steelhead,” the Council says. “There was an important Indian fishery at the mouth of Asotin Creek, just south of present-day Clarkston, Washington, and tribal fishers journeyed from the desert plains of southern Idaho to fish for salmon and steelhead in Snake River tributaries in the mountains of central Idaho. Salmon and steelhead spawned in the Snake River Basin as far upriver as Shoshone Falls, some 300 miles above Hells Canyon.”

The Council says it is difficult to say how many salmon spawned upstream of the Hells Canyon Complex historically, but fish counts at the Brownlee and Oxbow dams between 1958 and 1960 likely give some indication, although the numbers could have been higher 100 years earlier.

“At the time, the maximum counts were approximately 17,000 fall Chinook in 1958, 2,600 spring Chinook in 1960 and 4,500 steelhead in 1959 and 1960. Sockeye were extirpated with construction of Black Canyon Dam in 1924. There were no coho upstream of Hells Canyon historically,” the Council says.

When construction began at Brownlee in 1956, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game and the U.S. Department of the Interior sent letters to Idaho Power requesting fish passage for both upstream- and downstream-migrating fish at the Hells Canyon Complex, the Council says. Temporary upstream adult passage facilities were put into place at Brownlee and a fish trap using an electric barrier to guide fish to the trap was completed in December 1957.

“This trap was soon replaced by an adult trap at the Oxbow Dam construction site downstream in May 1958,” NPCC says, adding that the quick pace of dam construction was too fast for investigations that may have provided more information about the efficacy of fish passage, which would have been considered experimental.

“By 1958, when Pacific Northwest Power filed its license application for the High Mountain Sheep Dam, Idaho Power had decided that [the] best option for the Hells Canyon Complex would be trapping and hauling the fish as opposed to constructing fish ladders or fish elevators,” according to Council. “While passage of adult fish was successful, passage of juvenile fish migrating downstream was not.”

In author Susan M. Stacy‘s 1991 book “Legacy of Light: A History of the Idaho Power Company,” the untried fish barrier system consisting of a net stretched across the pool at Brownlee was ready for operation in 1959, but problems started right away.

“First, the net ripped early and often. Idaho Power hired a crew of three divers, who submerged regularly to make repairs and remove moss and other material suspended in the newly formed reservoir,” Stacy wrote.

In addition, officials at the time did not think fish would dive below 100 feet so the net was not constructed to reach the bottom. That summer, the temperature in the Hells Canyon reached 117° and they were proven wrong, Stacy added.

“Fish dove below the net and ended up being killed in the Brownlee turbines,” according to Stacy, adding that then there were issues with getting the fish to the net. Juvenile fish especially had a difficult time traversing their way to the net skimmer because the reservoir is about 57 miles long and there was virtually no current.

Stacy added that fishery officials made one other critically erroneous prediction that had negative effects on the anadromous fish.

“They thought the fall migration of chinook salmon through Hells Canyon up to their spawning waters was a fairly minor run, consisting of not more than eight percent of the total Columbia River stock, far fewer than the number that spawned up the Clearwater River to the north,” Stacy wrote. “They were taken somewhat by surprise when an unfortunate accident demonstrated just how many salmon migrated to the Snake.”

In August of 1958 during the construction of Oxbow Dam, water rushing through a cofferdam eroded the rock and placed the fish trap in jeopardy. Idaho Power ordered the cofferdam to be blasted, which placed the Oxbow construction work under 60 feet of water and halted the project, Stacy says.

As the fall chinook began to arrive, nylon nets were used to catch the fish. When the trap was repaired, Stacy wrote, the river was once again diverted through the tunnel, and water at the construction site receded. This exposed a deep cavern in the loose rock and stranded an estimated 3,700 fish.

“The company rushed air compressors to the pool to supply oxygen, and netted 1,000 live fish. About 2,700 fish died, along with a few hundred others that had been trapped in other pools,” Stacy says. “The loss represented about 15 percent of the fall chinook run for that year.”

Following that incident, the trap reportedly worked as intended and approximately 13,000 fish were hauled around Oxbow to Brownlee Reservoir. That high number, Stacy says, surprised fishery officials. The trap also caught other fish, considered “trash” at the time, and she says “at times were estimated at 40,000 in one day.”